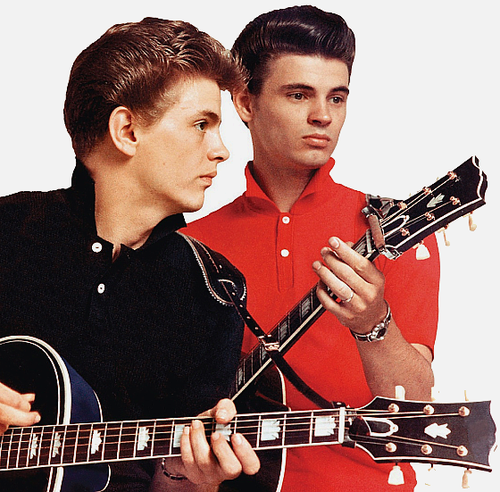

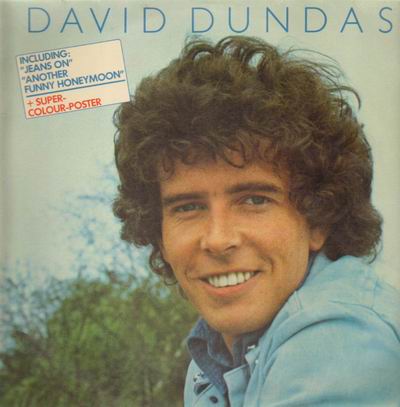

music

music

Well, my audience is only limited in size, not strength of character

music

music

extended status update memes

extended status update memes

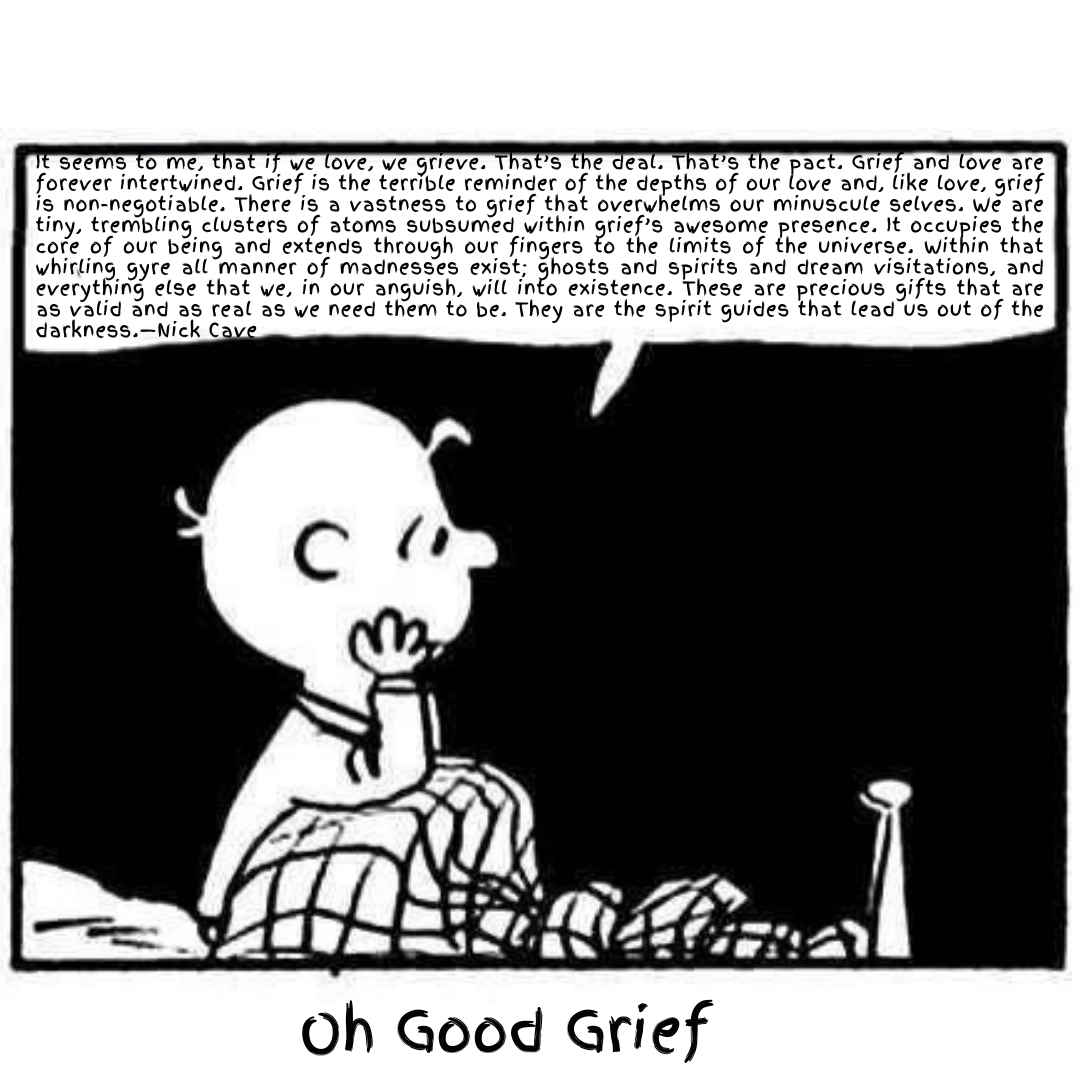

Oh Good Grief

hell is other people

hell is other people

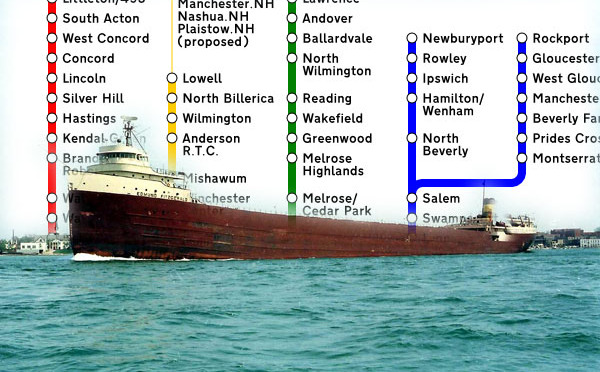

Lowell Rebrands

music UU

music UU

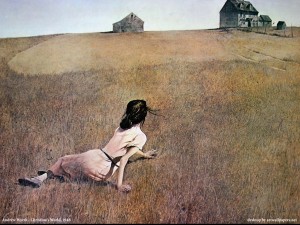

The True Protest Is Beauty

books

books

The Bathroom At Connie’s Wedding

hell is other people memes news

hell is other people memes news

Thanks, Don Bailey

memes

memes

The Morris Day After

performance

performance

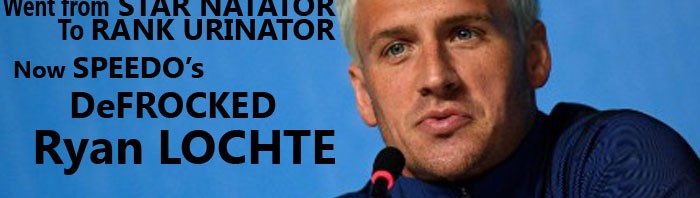

Larry Vaughn 2016

memes news social media

memes news social media

“I Believe in America.”

memes

memes

Star Trek 237

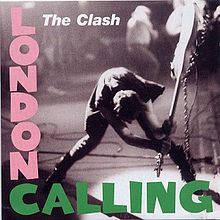

music

music

The Hitcher: David Allan Coe

books

books

Editing Eliot: A Prufrock Challenge

hell is other people memes photo essay

hell is other people memes photo essay

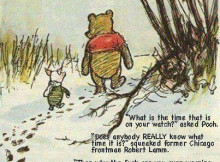

Poohcago

books music parenting and family

books music parenting and family

Jingle Balrog

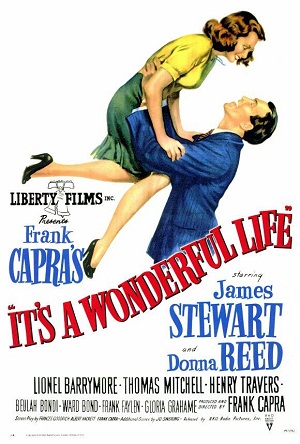

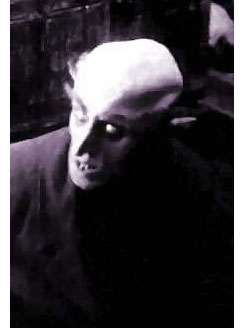

memes movies

memes movies

The Kindness of Black Holes

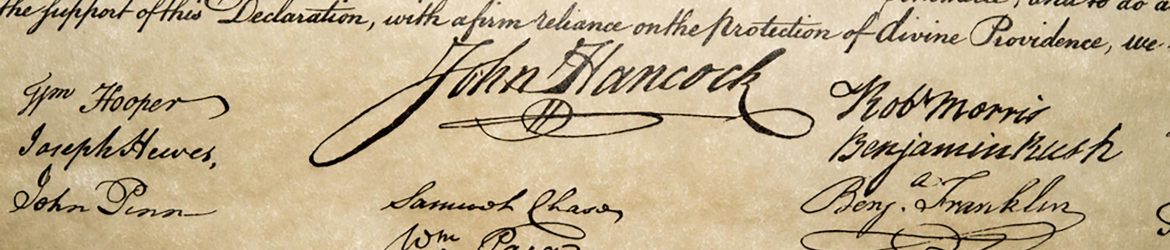

history movies

history movies

June 29: Ichthyology Numerology

food

food

The Green Beans of Courage

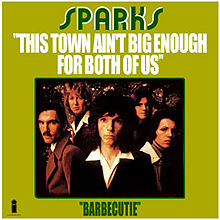

music

music

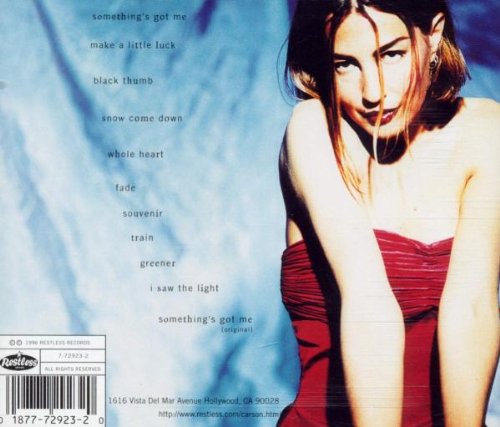

“Black Thumb”: Lori Carson

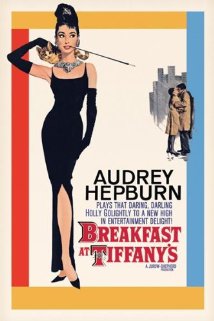

movies music video

movies music video

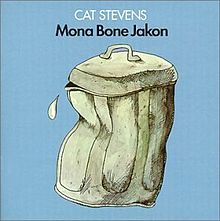

“Katmandu”: Cat Stevens

music

music

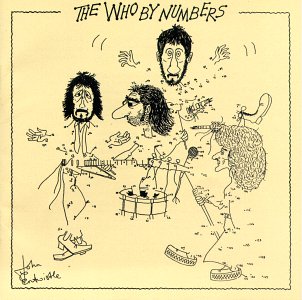

“Blue Red And Grey” by The Who

music video

music video

“Mr. Blue Sky” by ELO

music

music

“The Crystal Ship” by The Doors

music

music

“Thursday” by Morphine

memes

memes

Resume Tips from Mother Theresa

memes

memes

Where Is This Child’s Father?

books commerce

books commerce