Every writer can get into bad habits, but just remember what your best English teachers (mine were Mrs. McGovern, Mr. Molleur, Miss Hallissy, Mr. Kealy, Ms. Hylen, and Professor Goldstein) told you: Think about what you write so that you’re not writing anything unnecessary.

Today a writer I work with sent me an article containing the phrase “almost Pavlovian.” The writer described responding in a certain way when the phone rang.

Let’s just call that Pavlovian, because the reader understands that you are not a dog whose stomach has been turned inside out for researchers to better view the flow of saliva. That you responded in a set way to a certain stimulus is Pavlovian.

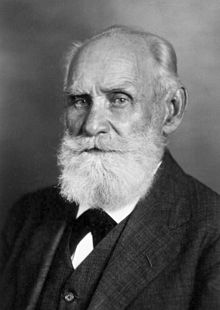

Ivan Pavlov’s experiments with doggies in the first decade of the 20th century involved conditioning the animals to associate the ringing of (dinner) bells with food. A bell would ring and food would be provided. Soon, tricky Pavlov got the dogs to start drooling just by ringing the bell. To check his work, he turned the dogs inside out, “Hellraiser” style.

The writer also wrote “veritable plethora.” In today’s economy, we no longer have the means to verify each plethora, so must rely on trust that the plethora in question is, in fact, one. Just write “plethora” or, if you don’t want to sound like a pretentious ass, “a lot.”

“Yeah, when you call my name/I salivate like a Pavlov dog,” sings Mick Jagger, explaining the causal relationship between your addressing him and his drooling. He did not see the need to qualify as “almost Pavlovian” his response, even though there was no bell. You called, he salivated. Pavlovian.