At breakfast, I remembered that it was the 249th anniversary of the Boston Massacre.

At breakfast, I remembered that it was the 249th anniversary of the Boston Massacre.

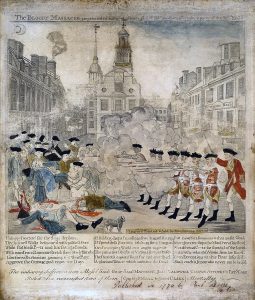

On March 5, 1770, a mob of Bostonians taunted a small group of British soldiers gathered by the Boston waterfront. As the crowd grew, hurling rocks and snowballs packed with oyster shells, the troops were reinforced by soldiers bearing muskets with fixed bayonets. Nearby fire bells were rung to disperse the rabble. A soldier—but not the group’s commander—yelled “fire already,” and the soldiers unloaded into the crowd. Five people died, including Crispus Attucks, a former slave.

My girlfriend and I were eating horrible egg white omelettes alongside bowls of joyless oatmeal, as I have been sentenced to a punishing diet in my creeping decrepitude. Through my tears I said, “Oh! It’s March 5, the 249th anniversary of the Boston Massacre. So that’s something.”

My girlfriend, who speaks five languages, said “Oh,” in French.

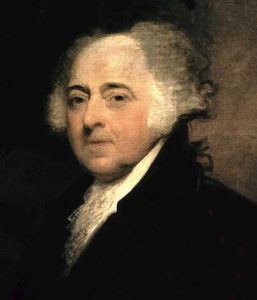

“John Adams defended the British soldiers five years before the American Revolution began,” I said. “He was against the British being there, but he knew that the soldiers deserved a fair trial, otherwise the resistance would lack legitimacy.”

“That’s interesting,” she said, in the detached way one might announce one is dying, alone, in a world full of strangers and regret.

“Paul Revere circulated this flyer that showed the redcoats firing into the crowd,” I said. “It was some incendiary propaganda.”

“Huh.”

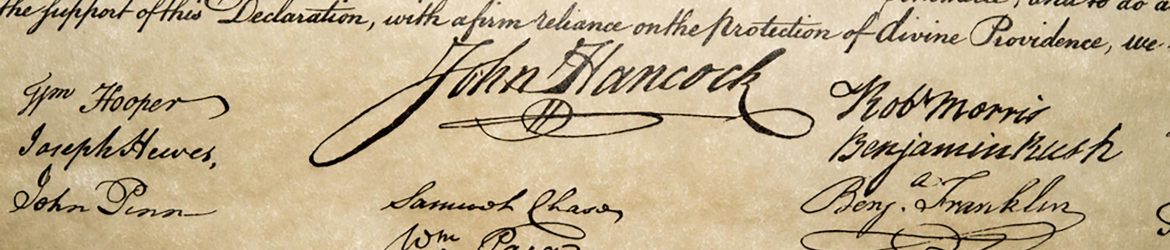

“I read David McCullough’s biography of John Adams,” I said. “It was fascinating. He and his wife, Abigail, wrote wonderful letters to each other. When he was in the Continental Congress that drafted the Declaration of Independence, Abigail reminded him in a letter to ‘remember the ladies’ when he and his buddies were going around creating a new country. Of course he didn’t, but they are great letters.”

“How nice!” she said, contemplating the doom that awaits us all.

“There was a great HBO series with an excellent theme song. David Morse played George Washington, Laura Linney played Abigail, and — — ”

Wait. Who played John Adams?

It was 7:15 a.m. I’d come up short on names before, and pieces of music. In 1993 I spent six pre-internet months trying to remember the theme song from “Fish.” I knew I could remember this guy’s name.

“Bart Sugarman,” I said.

“That has a B and an R in it,” she said. “It’s not Bart Sugarman.”

“Bert Schneider.”

“No.”

“Roger Brunelle.”

“No.”

“He was in ‘Straight Outta Compton.’ He gets these uber-nebbishy roles. Oh! He was Harvey Pekar in ‘American Splendor’ and his wife was Hope Davis. I liked her in ‘Next Stop, Wonderland’ and ‘The Imposters.'”

Why could I remember all these other things but not the real name of Bart Sugarman?

“He’s an excellent actor. A James Cromwell-level character actor. God damn it! His father was the commissioner of major league baseball after Peter Ueberroth!”

There is no reason that I could recall the names of three former major league baseball commissioners, but I did: Kennesaw Mountain Landis (as a result of reading Philip Roth’s masterful “The Great American Novel,” about the doomed Port Ruppert Mundies), Peter Ueberroth, Bart Sugarman’s father, and the guy who succeeded him following the latter’s heart attack, Fay Vincent. And wasn’t it interesting that Philip Roth and Peter Ueberroth had similar names, as if the latter were more Roth than the former?

There is no reason that I could recall the names of three former major league baseball commissioners, but I did: Kennesaw Mountain Landis (as a result of reading Philip Roth’s masterful “The Great American Novel,” about the doomed Port Ruppert Mundies), Peter Ueberroth, Bart Sugarman’s father, and the guy who succeeded him following the latter’s heart attack, Fay Vincent. And wasn’t it interesting that Philip Roth and Peter Ueberroth had similar names, as if the latter were more Roth than the former?

What was once a blind spot had crept. I have a feeling (though I can’t be sure), that if you’d asked me to name some MLB commissioners before the 249th anniversary of the Boston Massacre, I would have easily named Bart Sugarman’s dad. But today it was a swing and a miss.

In Roman times there was something called the Damnatio Memoriae, in which names, likenesses, and whole family histories of disgraced individuals would be erased from columns, from public records, and from speech. It was like an embargo on memory. I felt that Bart Sugarman had just erased his dad. When would he stop?

I’d recently begun taking a statin for high cholesterol, thus my terrible new diet. I’d experienced no side effects, thankfully, like the muscle pain and headaches listed as potential contraindications, but I was worried about memory loss, which is also a possibility. When I was prescribed this medication, I asked my doctor if I was going to lose my damn mind.

“Why would that happen?” he asked, not caring if I lived or died.

“Well, memory loss,” I said.

(Millions of people voted for Donald Trump, too.)

It had been an hour and I was getting angry with myself. I thought that the first name was a single syllable and the last name was somehow distinctive. I kept almost catching it.

My girlfriend said, “Do you want me to tell you? I don’t think I should.”

“You’re right,” I said. “You shouldn’t.” Partners should encourage each other, not enable weak behavior.

I felt that the first name wasn’t something memorable—Oh! He was also in a Kevin Spacey movie about a hostage negotiator—, This guy had a first name that didn’t suggest the type of roles he played. Like Steve Buscemi. It was the last name that mattered. Was the last name Italian?

It was 8:15 and we were now in the car, heading east on Ball Road in the lovely city of Anaheim. Back in 2000, a colleague had referred to this area as “Crapaheim.” Why do I remember everything else? In 1997, shortly before I introduced him to the woman he would marry, my friend Bob and I were driving and he played the other song by the band Chumbawamba, “Amnesia.” I remember Bob, his wife, Lisa, the names of their two wonderful daughters and where the accents go in the Gaelic spellings of their names, and a funny story about something Bob saw when he was deployed in Afghanistan.

“Paul Giamatti.”

I saw the “Poll” in “Pollo” and it came to me. Paul Giamatti’s father was nicknamed Bart. I don’t know where the Sugarman came from, unless I’ve heard Giamatti pronounced with three syllables instead of four. I wonder why, like an adaptive virus, the name seemed to become more and more resistant to my attempts to remember it.

“Finally,” my girlfriend said, wondering if she should call these things “episodes,” “spells,” or “setbacks.”

Later that morning, in open defiance of my diet but in humble observance of Mardi Gras, we had Vietnamese sandwiches. The extreme emotional effort of remembering Paul Giamatti’s name had left me exhausted, and French-occupied was as close to French as we could get.

Goddamn beautiful.

Some day we will return to the Granary Burial Ground and toast Crispus in person.

This is all very well, but let’s leave the French out of it.

P.S.: When, swept up in your preternaturally vivid prose, I found myself ACTUALLY SUDDEN FORGETTING *THAT MAN’S* NAME, I forced myself to try to remember it–unaided. No cheats. Glanced (involuntarily, I swear!) a few lines ahead, saw “Pollo,” and the rest suddenly fell into place.

Either some definitive form of New-Englander-wise-ass-neuro-homogeneity is a REAL thing…OR this is simply the way the aural/oral/associative brain works.

(That or–more like–we’re all living in a vastly-advanced computer simulation devised 13 billion years ago by Abe Vigoda.)

YES. It wasn’t until I saw the sign (like that post-ABBA Hope-of-Sweden Neo Nazi group Abe of Babb) and pronounced it incorrectly that I got the “Paul.”