When Langston Hughes wrote “I loved my friend/He went away from me/There’s nothing more to say/The poem ends/Soft as it began/I loved my friend,” he had it easy.

If you are reading this in 2013, congratulations! You and I are in the first generation of social networkers. And, while we are pioneers in navigating the etiquette of spamming, tagging, inviting, oversharing, vaguebooking (“Somebody better check himself. You know who you are”), and posting our lunch and location—all points on a very public learning curve—until recently we were assured—at least on Facebook—that we could unfriend someone in secret.

I have made many newbie mistakes on Twitter and Facebook; I have leapt into political conversations with people I neither know nor agree with, I have forgotten to keep the mood lite, I have been a little too exploitive of my photogenic pets, and—worst of all—I forgot to say No.

This last mistake made me decide to quit Facebook a few years ago, when I had 3,000 friends and zero active privacy settings. My friends list had long overtaken real friends, bandmates, work associates old and new, high school and college friends, high school and college acquaintances I never liked, friends and relatives of friends who didn’t know me but had heard stories, people I met at shows, my ex-wife’s exes, my own exes with whom I shared really good reasons for being exes, former teachers who were somehow still clinging to life, and Lee Fierro, who played Mrs. Kintner in “Jaws,” whom I didn’t know but wanted as a Facebook Friend.

This last mistake made me decide to quit Facebook a few years ago, when I had 3,000 friends and zero active privacy settings. My friends list had long overtaken real friends, bandmates, work associates old and new, high school and college friends, high school and college acquaintances I never liked, friends and relatives of friends who didn’t know me but had heard stories, people I met at shows, my ex-wife’s exes, my own exes with whom I shared really good reasons for being exes, former teachers who were somehow still clinging to life, and Lee Fierro, who played Mrs. Kintner in “Jaws,” whom I didn’t know but wanted as a Facebook Friend.

Because in those first years after it broke out of Harvard, Facebook was all about collecting.

So after a while I quit, because I knew maybe 10 percent of those 3,000 people. Then, about nine months later, when I had a show to promote, I crawled back, ashamed, to find that my account was miraculously still there; Facebook didn’t even pretend to have deleted it like I’d very specifically asked. Facebook knew.

But this time I vowed to do things differently. I would establish rigorous privacy settings and control who could contact me. I would never accept a friend request from someone I didn’t know and at least sort of like. And I would never let my friends list get beyond 500 people.

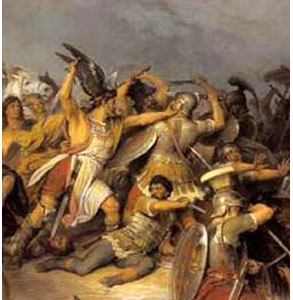

To this end I began a regular schedule of purges, wherein every six months I would follow the Roman Army’s lead and carry out decimations. When your army lost to Rome, not only would you and your comrades march under the yoke to show your subjugation, but the Romans would kill ten percent of your buddies. Today some people (I’m vaguebooking here) use the word “decimate” to mean destroy utterly, like “The Dodgers decimated the Yankees,” but as a Latin scholar I knew that every six months I would trim just 10 percent from my friends list, not destroy it utterly.

To this end I began a regular schedule of purges, wherein every six months I would follow the Roman Army’s lead and carry out decimations. When your army lost to Rome, not only would you and your comrades march under the yoke to show your subjugation, but the Romans would kill ten percent of your buddies. Today some people (I’m vaguebooking here) use the word “decimate” to mean destroy utterly, like “The Dodgers decimated the Yankees,” but as a Latin scholar I knew that every six months I would trim just 10 percent from my friends list, not destroy it utterly.

And this was not difficult. Sure there were people who couldn’t stop talking about punching liberals in the face, but most of my cuts were of people who’d made a friend request whom I’d never heard from again, or who only posted their Farmville scores, or who never posted at all, having exhausted themselves with the effort of creating a Facebook account and fallen back, limp, without having uploaded a profile photo.

I called that sluggish pool of non-participatory profiles Friendbloat, and vowed to cut the fat twice a year.

So you know I was not heartless, I had a code. Facebook’s birthday notification service was nine out of ten times the thing that reminded me I didn’t want to be friends with the birthday boy or girl. I would write down the name and wait until June or December 1, the Decimation Days. I wouldn’t cut someone out on their birthday; it was similar to the Mob code of not killing someone in front of his family, except with way too many cupcake pictures with “Nom nom nom” under them.

But until recently I could have unfriended someone in secrecy. Twitter and Instagram have services like JustUnfollow, that can both unfollow people who haven’t followed you and alert you to when you are unfollowed. This seems reasonable for a platform like Twitter, which never said you have to be friends with someone to follow them.

But until recently I could have unfriended someone in secrecy. Twitter and Instagram have services like JustUnfollow, that can both unfollow people who haven’t followed you and alert you to when you are unfollowed. This seems reasonable for a platform like Twitter, which never said you have to be friends with someone to follow them.

For Facebook, however, I could deal with creeping Friendbloat silently. These people would never know I was no longer their friend because they hadn’t interacted with me at all. Once or twice someone I’d subjected to decimation would send me another friend request a few months later, sometimes accompanied with an “I don’t know how we fell off each other’s list.” Ha ha ha.

Then this summer I began getting messages like this:

Did I do something to offend you?

People knew I was unfriending them! What’s worse, very often this indignant message, which showed up in the “Other” ghetto of Facebook mail, was the only actual communication I’d received from a person following their initial friend request.

I’d send a message back, something not suited for a breakroom Peanuts poster, that explained that Facebook friendship isn’t actual friendship. Actual friendship, I’d say, involves your knowing my children’s names. No offense, I’d add, but our lack of any pithy interaction over a years-long period indicated to me that you weren’t a Good Facebook Friend.

Some of my best real friends are horrible Facebook friends, I’d point out, to soothe them.

I found the browser plugin Social Fixer, a 3rd-party device that cleans Facebook pages of certain ads, eases data entry, tabs sources, and genuinely adds functionality to the interface.

I found the browser plugin Social Fixer, a 3rd-party device that cleans Facebook pages of certain ads, eases data entry, tabs sources, and genuinely adds functionality to the interface.

But it also tells you when someone has unfriended you (or has left Facebook). Thus those several hurt messages. These people were saying, “Just because I have had nothing to do with you for years doesn’t mean you’re not in my heart.”

I understand, but I want vigor in my online relationships. I want to really want to forward that Someecard.

I’m all right for now. The last decimation is over and I have about 448 friends. But in a while that number is going to creep up and I’ll get a birthday alert for some zealous go-getter whom I met at a conference and, in a flurry of business cards and drink invitations, friended me right then and there, and then blew out of my life.

And I will want to write down that name for my anti-Friendbloat Decimation List, because I know that person doesn’t care about me, or my dog, or my adorable children, or the Squeeze lyrics I occasionally post; who will not give me a recommendation on a place to buy Framboise Lambic on tap—or even shame me for wanting to do that, who will not, when I go through that awful process of re-learning the code that invites everyone on my friends list to a show, even look at the invitation, whose children I have nothing kind to say about, who has just married a mail-order bride, who writes “your” instead of—well, you know.

Come December, I’ll just have to be friends with everybody.

One Reply to “Socialized Medicine: Friendbloat No Longer Curable with Facebook Decimation”